Our first big day of football is under our belt, and one of the storylines from yesterday was turnovers, specifically fumbles. Oregon lost 3 fumbles in their loss to #4 Georgia. Two of Notre Dame’s 5 turnovers were lost fumbles, including a backbreaking fumble on 3rd and 1 from the USF 1 yard line that was returned the length of the field for a TD. I tweeted that that fumble alone was worth an 11.2-point swing in USF’s favor (for those curious, the start of the play [3rd and Goal at the 1] is worth about 4.9 expected points, and the end of the play [a USF TD] is worth -6.3 points for a total swing of 11.2 points). Clearly ND’s running back Jonas Gray was fighting as hard as he could to get the TD, but was stood up by 5 defenders and eventually stripped of the ball. The result was disastrous for the Irish.

Our first big day of football is under our belt, and one of the storylines from yesterday was turnovers, specifically fumbles. Oregon lost 3 fumbles in their loss to #4 Georgia. Two of Notre Dame’s 5 turnovers were lost fumbles, including a backbreaking fumble on 3rd and 1 from the USF 1 yard line that was returned the length of the field for a TD. I tweeted that that fumble alone was worth an 11.2-point swing in USF’s favor (for those curious, the start of the play [3rd and Goal at the 1] is worth about 4.9 expected points, and the end of the play [a USF TD] is worth -6.3 points for a total swing of 11.2 points). Clearly ND’s running back Jonas Gray was fighting as hard as he could to get the TD, but was stood up by 5 defenders and eventually stripped of the ball. The result was disastrous for the Irish.

When considering whether to fight for the extra yard, there are two main trade-offs: fumbles and injuries. Going down or out of bounds as opposed to battling one or more defenders would decrease the likelihood of a fumble as well as save the runner’s body from both acute injury and repetitive wear and tear. In this post, I’m going to consider only the trade-off of the extra yard versus the risk of fumbling. The example above represents one of the biggest risk-reward situations in this area, where success means a TD and a fumble is extra costly. Other areas to consider: going for a 1st down, yards inside the 1st down marker, and yards after a 1st down has been gained.

What’s a yard worth?

The first step in evaluating this issue is to determine the value of the extra yard. Each yard inside the 1st down marker does two things: (1) it moves you closer to the goalline and (2) it moves you closer to the 1st down marker. The final yard for a 1st down not only moves you closer to the goalline, but gives you a new set of downs as well. Finally, each yard after the 1st down marker simply moves you closer the goalline–wherever you end up will be a 1st and 10.

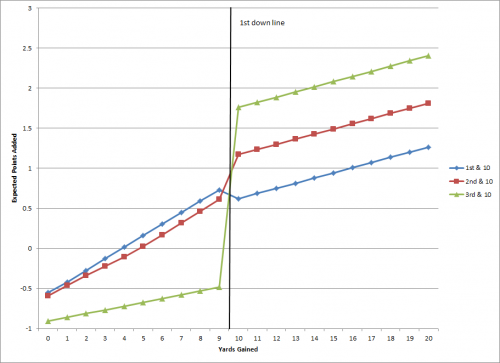

This first chart shows the Expected Points Added (EPA) from the initial starting point (either 1st and 10, 2nd and 10, or 3rd and 10) by number of yards gained (NOTE: I am using NFL expected points from AdvancedNFLStats, though college numbers would tell a similar story). The line has the same slope inside the 1st down marker (first 9 yards), makes a jump at the 1st down marker, and then has a flatter slope after the 1st down has been achieved.

But wait, is that a downward jump on the 1st and 10 line right at the 1st down marker? Is 2nd and 1 better than 1st and 10 one yard closer? Yes, it may sound counter-intuitive, but this same paradox has been discovered before.

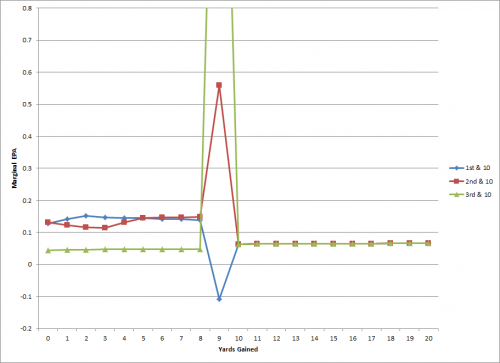

Let’s look at the chart from the aspect of marginal EPA. That is, the difference between the EPA of gaining, say, 5 yards and the EPA of gaining 6 yards. In this chart, each “yards gained” value is compared to that of the following yard. For example, the value listed at 5 yards gained is the difference between the EPA at 5 yards gained and 6 yards gained. The large spikes occur at 9 yards, where the difference is between a 9-yard gain leaving 1 yard to go and a 10-yard gain for a 1st down. The 3rd & 10 spike is over 2 points (2.2 to be exact), but I cut it off to accentuate the other parts of the graph.

Each yard gained after the 1st down marker is worth about .06 to .07 points regardless of the down you’re on, while each yard gained on 1st or 2nd down up until the 1st down marker is worth about .14 points, about twice as much. However, yards gained on 3rd down before the marker are worth just .05 points. This makes sense since the team is likely going to have to punt following the play.

When is the extra yard worth it?

To simplify the question, I’m going to assume the runner has a choice. He can either go down or out of bounds at the yard line he’s at, or he can fight for the extra yard at the risk of fumbling the football, which if the defense recovers it would be at the yard line of the extra yard. For example, if it’s 1st and 10 at the team’s own 20 and they have run for 5 yards, the possible outcomes are: (1) go down for a 5-yard gain, no fumble, 2nd and 5 from the 25, (2) go for the extra yard and don’t get it, 5-yard gain, 2nd and 5 from the 25, (3) go for the extra yard and get it, 6-yard gain, 2nd and 4 from the 26, or (4) go for the extra yard but lose a fumble, opponent’s ball 1st and 10 on your 26.

A lost fumble on a running play happens around 0.7% of the time, or about once every 143 attempts. Given that as the probability of losing a fumble when going for the extra yard, we can now produce the breakeven point for how likely it is that you will need to get the extra yard to offset the risk of turnover.

| Down | Area | Extra Yard | Lost Fumble | Breakeven% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Inside 1st Down | 0.14 | -3.92 | 19.6% |

| 1st | At 1st Down | -0.11 | -4.32 | -28.6% |

| 1st | Outside 1st Down | 0.06 | -4.19 | 46.0% |

| 2nd | Inside 1st Down | 0.13 | -3.27 | 17.4% |

| 2nd | At 1st Down | 0.56 | -3.66 | 4.6% |

| 2nd | Outside 1st Down | 0.06 | -4.19 | 46.0% |

| 3rd | Inside 1st Down | 0.05 | -2.05 | 31.0% |

| 3rd | At 1st Down | 2.24 | -1.97 | 0.6% |

| 3rd | Outside 1st Down | 0.06 | -4.19 | 46.0% |

In order to go for the extra yard after you’ve already notched the 1st down, you should be at least 50/50 to get it. Compare this to inside the marker, where the runner needs to only have about about a 1-in-5 chance of getting the extra yard on 1st or 2nd down. On 3rd down, the runner needs to have a little better chance, around 1-in-3, in order to make it worth it.

At the marker, I have already pointed out the fact that 2nd and 1 is better than 1st and 10 according to the EP model, so the runner should never attempt to gain the extra yard. On 2nd down, you need to have just a 5% chance at the 1st down in order to go for it. On 3rd down, the runner might as well go up against all 11 defenders if need be, the 1st down is extremely valuable in that situation since not converting will bring up 4th down.

Conclusion

This is a very simplistic analysis of this topic. For one, rarely is your decision on the football field between going down or possibly getting just one more yard. Many times you can fight for 2, 3, 4 yards or even break a tackle or two and gain a large chunk of yards. “Fighting” for the yard could range from stretching the ball out, diving for the marker, taking on one defender, or taking on numerous defenders. Each scenario would affect both the chances of conversion and the likelihood of a fumble. I did not even touch on the possibility of injury, which not just impacts the player getting hurt but can also impact the team based on the dropoff to that player’s backup during the duration of his injury.

From a coach’s perspective, proper technique and concentration can minimize the possibility of a fumble, which is a much bigger factor in this whole analysis. In addition, instructing your players to not fight for each possible yard is in many ways in contrast with everything else coaches preach about toughness, perseverance, and doing everything possible to win.

With all of those caveats, I would offer this advice:

- Players with the football, especially receivers catching the ball over the middle of the field, who have already achieved a 1st down, should often get down or out of bounds when meeting multiple defenders. Marvin Harrison often did this to protect both himself and the ball.

- On 1st and 2nd down, runners should almost always fight for each extra yard, but should not reach the ball out and further risk a fumble. On 3rd down, the strategy should be similar but once a 1st down is out of reach, a bit more conservative.

- On 2nd or 3rd down, runners who have a chance at a 1st down should do everything in their power including reaching out the football or diving for the marker to convert.

- A team’s top players, should be more conservative than average since an injury would affect the team while they’re out. This is the reason QBs in the NFL slide, and often RBs and WRs duck out of bounds rather than take an unnecessary hit. Except in the highest leverage situations–near the goal line and near the 1st down marker on 2nd and 3rd downs–QBs should continue to slide and other ballcarriers should be smart about the hits and risks they take.

Jonas Gray possibly could have had better technique in holding onto the ball, but the main reason he lost the ball was that he took on multiple defenders in order to fight for the extra yard. In this situation, it was the right play but with an unfortunate outcome that turned the tide of the game–and possibly Notre Dame’s entire season. Next time he should concentrate on holding onto the ball better, but should continue to fight for those yards when the situation dictates.

Excellent analysis, Monte (just found this site from Tango’s blog)

You took 0.7% as the fumble rate for fighting for the extra yard. Wouldn’t that be higher? I don’t have the numbers in front of me, but doesn’t the sample include some instances of running out of bounds/not fighting for extra yards. In fact, couldn’t that be a significant part of the sample?

I suspect the fumble rate on “fighting for the extra yard”, particularly in the case where it is clearly a player’s decision, could be higher, perhaps as high as 3%.

What do you think?

DSMok1/1

Thanks for the kind words. Absolutely, I agree with you that the 0.7% is probably low in these situations. I was more interested in getting the relative weighting between the three main situations: inside the 1st down marker, at it, and after it. Perhaps if I do a follow up, I will try to better estimate the fumble percentage, as well as try to quantify injury risk to come up with a more definitive answer.